by Priest John Whiteford

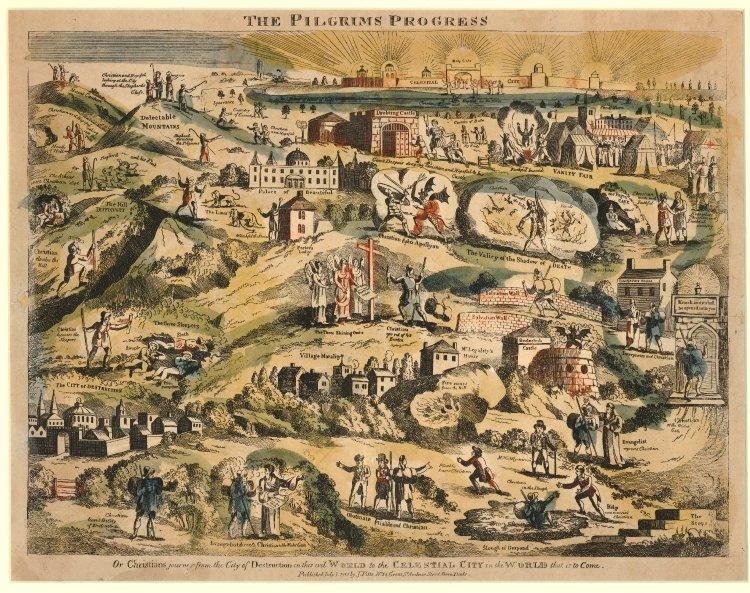

A map of the journey of Christian, from Pilgrim’s Progress

A map of the journey of Christian, from Pilgrim’s Progress

I was raised in a very religious Protestant home, a fifth generation Nazarene… which means that my family (on my mother’s side) has been in that denomination about as long as it has existed. In my home, my mother, four brothers, and I, with very rare exception, attended Sunday School, the Sunday morning service, the Sunday evening service, Wednesday night prayer meetings, and we were there every night of the week when there was a “revival” going on, which was not infrequently.

My father also came from a very religious background – the “Campbellite” Church of Christ. He was born in Texas, grew up in Missouri, and then moved with his family to California during the Dust Bowl period. He was a World War II veteran, who made a very good living as a pipe-fitter and insulator who worked with asbestos. He knew the contents of Scripture better than my mother did, but by the time I was a child, he rarely went to Church, and when he did, he went to the Nazarene Church with the rest of us. I discovered later that he fit into a pattern I have observed in people associated with that denomination – he had reached the point that he decided that most churches were filled with hypocrites, and so felt no need to have anything to do with them, but he maintained a faith of his own. As a result, he did not have much of an impact on my religious education, beyond telling some stories about some of the controversies that raged in the Church of Christ (stories very similar to those I later heard from other burnt out former members of that Church), and my recollection of certain passages of Scripture he was fond of quoting.

My parents divorced when I was about 6, and then when I was 9 my mother moved me and my brothers from California to Murray, Kentucky. She was a good bit younger than my father, and was from Chicago, but decided to move to Murray because her mother had retired there. Aside from that, however, it was not a very practical decision, because there wasn’t much work to be had there. The nearest “big city” was Paducah (which is right between Possum Trot and Monkeys Eyebrow), and we were about 50 miles further into the boonies. Economically, this was a big step down for us. We had literally lived on Country Club Lane, in a suburban Southern California town (Grand Terrace), and now we had moved to Tobacco Road. This small town in western Kentucky was not a very welcoming place for outsiders. We were considered “furnurs” (foreigners). In my first year there, the 4th grade, I got into 52 fights. I remember the number, because I kept score on my desk to scare off challengers (49 wins, 3 losses). Two years later we moved to Houston, where one of my uncles lived, and where work was much more plentiful. Had I moved from California straight to Texas, I might not have liked it nearly so much, but after two years in Murray, Kentucky, I quickly came to love it.

From my earliest childhood, well into my teens, my mother always read to us in the evening. When we were younger, she read Bible stories. As we got older she read other books that she thought would be edifying, such as stories about missionaries in Africa. In the eighth grade I began reading the Bible on my own, from cover to cover, and read it through several times before I was half way through High School. However, I was curious about other religions too, and began reading about them at an early age. One of the things I did when I was bored as a child was to flip through the World Book Encyclopedia, and read anything that caught my attention (this was in the days before video games, VHS, DVDs, DVRs, and the Internet). I remember reading the article about the “Eastern Orthodox Church” before I moved from California, so some time before I was ten. So I knew that such a Church existed, but didn’t think too much of it. I figured it was a more exotic form of Roman Catholicism… and in my home, we were pretty much taught that Roman Catholics were idolaters, and that when they died they just took them down to the basement and put them into a chute straight to hell.

At the age of twelve I became interested in Islam, because of some Iranian students who lived in an apartment complex we had moved to. Then, I studied Judaism. In the eighth grade I took a correspondence course from the Knights of Columbus, and studied Roman Catholicism. Despite what I had been taught, I found it attractive on many levels, but could not square it in the end with what I believed Scripture taught.

In the ninth grade, I got to know a United Pentecostal girl who I had a crush on, and she invited me to her Church, and so I went. The first service I attended happened to be the first Sunday of the new year, and when the pastor got up to speak he said “I know most of us thought we would never see this day come… but this year, something’s gonna happen… that’s a prophecy!” A few weeks later, they had an “evangelist” come and preach. It seems he was not getting the emotional reaction that a successful sermon was expected to have, when he began to declare “Someone is gonna die tonight! God has told me that there is someone here tonight that – if they don’t come down to this altar [in Evangelical circles, this is a kneeling rail] and repent, they are gonna die… tonight! You’ve been committing the same sins, over and over again, and God is giving you just one more chance.” I was used to sermons designed to scare the pants off of you, but this was on a whole new level. So for a few months, I really got into this Church, sang in the choir, and attended pretty much every service. However, as time went on, and emotions began to fade… and nothing developed with the girl who had gotten me to go there in the first place, I went back to my old Nazarene Church.

Years later, my mother’s friend from work, who happened to be a United Pentecostal asked me to go to Church with her on a Sunday evening. By that time I was in college, studying to be a Nazarene minister, but I went, mostly out of curiosity and a little bit of nostalgia. It just so happened that this was the first Sunday of another new year, and – I am not making this up – the pastor got up and said “I know most of us thought we would never see this day…” and before the night was through I heard another “Someone is gonna die tonight” message that was remarkably similar to the one I had heard in the Ninth grade.

Later in high school, I got a job in a bookstore, and because it was my job to check new books in, I acquired a number of new interests. For example, I began studying Japanese, because of a book that I ran across that explained how to read and write the Kanji (which are the characters borrowed from Chinese). Since there were no Japanese people around that I knew, but there were a number of Chinese students, I switched my study to Chinese, and that is how I eventually met my wife (though we did not begin dating until after I was out of high school). I also became interested in the martial arts, eastern mysticism (Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism), and even the Occult. I strayed very far from God during that time, though I continued going to Church regularly (because the idea of not going to Church was something that my mother’s strict discipline had beaten out of me many years prior). I should point out that I never could bring myself to directly deny Christ. During that time, when people would ask me what religion I was, I would say that I was a Christ-zen (kinda Christian… kinda Buddhist). And though I had hypothesized that perhaps Christ was another incarnation of Krishna, or the Buddha, I could never quite reconcile what I knew about Christ from Scripture with these non-Christian ideas, but I chose to simply shrug my shoulders, and leave that question unresolved, because I knew that there had to be something more to the spiritual life than I had yet experienced, and I hoped that maybe I was finding it in these other religions. I had little idea of Biblical scholarship at that time, but I had heard enough from those who raised doubts about the reliability of the Scriptures, that I figured that maybe some of the things in Scripture that did not fit with these other religions were simply errors that had crept in over the centuries. Despite these uncertainties, I had a sense that I was heading in the right direction, and a confidence that I had not known before. I was the master of my fate (I thought), but I was soon to learn differently… the hard way.

After I graduated from high school, my plan was to become a police officer (partly because I figured it would tie into my interest in martial arts). However, it just so happened that the Houston Police Department decided to raise the age of entry into the police academy that year, and so I was not able to go forward with that plan for the time being. So I simply began working full time.

The three big things in my life at that time were my girlfriend (not to be confused with my wife, whom I knew at this time, but had not yet started dating), Kung Fu, and the mix of Buddhist, Taoist, Hindu, and Occult ideas that I found so fascinating. I was very much into a Taoist book of divination, called the “I Ching.” I used it regularly, and thought that its predictions were remarkably accurate. One evening, however, all the indications from the I Ching were that horrible things were about to happen to me. Too much time has passed for me to remember all the details, but I do remember that one of the predictions was that my relationship with my girlfriend would end, though as of that point, nothing else had led me to think that was likely. For the first time, I had a sense that I was dabbling with something evil. It was almost as if I could feel the laughter of demons. I think that was the last time I used that book. Not many days later, something unexpectedly started a chain reaction in my life that seemed to fulfill the predictions of that evening.

I would often walk to work, because of the number of cars in the family, and sometimes just to save gas. One day, as I was leaving work at around 5:00 p.m., I was jogging on my way home, feeling really good, and was probably in the best shape of my life. I ran across a foot-bridge over Greens Bayou, and just on the other side there was a tree. On a whim, I decided to do a jumping skip kick on the tree. I had done it before, and so didn’t think anything of it. It was not kicking the tree which was the problem, but the landing. I landed on my left foot, with all my weight, and the root of the tree caused my left ankle to twist, and I heard a loud “pop”. My ankle swelled immediately to the size of a melon, and I had to remove my shoe, and hop on my right foot to the nearest phone. I was unable to walk without crutches for some time thereafter. Obviously, Kung Fu was out of the picture for the time being. A few days later, my girlfriend broke up with me, and I began to sink into a very deep depression that went on for about six months. I could hardly eat during that time. I had thoughts of suicide on a regular basis, and couldn’t see any light at the end of the tunnel.

Eventually, it began to dawn on me that I was where I was because I had turned away from God, and so I began to repent. I finally began to again feel a peace and a joy that eventually overcame my depression, and got me out of the spiritual pit that I thought I would never be free from again. I burned all of my occult books, my rather complete collection of the works of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and any other books that I felt were not pleasing to God. I would reach a point where I had overcome the “big sins” in my life, but then God always had more that I hadn’t thought of that I began to repent of as well. I had a spiritual reawakening, that was very much in line with the tradition I had been raised in. And I began to feel a call to the ministry. In particular, I felt a call to be a missionary, and began making plans to attend Southern Nazarene University, and to major in “Religion” (which in Holiness-Movement-speak was a word the meaning of which could range from “Theology” to “spirituality” (thus the phrases “He got religion” and “give me that old time religion”)… it was not a “world religions” program). They have since changed the name of the program to “Theology and Ministry.”

Matushka Patricia, when a baby in Guizhou, China. She moved to Hong Kong at the age of 6, and to the United States at the age of 16.

That button she is wearing is a Mao button.

It was during this reawakening that I began to date my future wife, and before I went off to SNU, we were formally engaged to be married, though while I was at school we were separated by a good 500 miles, long distance was much more expensive then, there was no internet, and so we would talk for about 30 minutes a week, and otherwise communicated by letter.

I came to SNU with the convictions and zeal of a new convert, because I had reconverted, and the experience was so deep and powerful, that while I had many things I did not know, there were a few things that I no longer doubted. I no longer doubted the truth of the Christian Faith, the truth of Scripture, or who Christ was and is. But as I began my first semester, I had a sense that some of my professors were very anxious to pour cold water over their eager and zealous young students. In one class, a professor began his first lecture by talking about how the Jews had waited for centuries for the coming of Christ, but that when He came, they missed Him, because they had built up walls around their faith to protect it. And just like the Pharisees, he said, “you too have built up walls around your faith.” He then proceeded to explain that he was going to tear down those walls, so that we could build our faith on a surer foundation. In the coming months, I came to see what he had in mind, and I can’t say that I was a very cooperative participant.

When one of these professors would make a statement that I found questionable, I would go and research the issue, and then when the subject would come back up, I would mention what I had found. For the most part, my professors at SNU were open to having their views challenged, and the back and forth of these discussions spurred me to dig deeper into many foundational questions of theology and Scripture – questions that would probably have gone unexamined if my instructors had been more conservative Nazarenes.

Many of my classmates struck me as very passive, and seemed to just accept what they were taught as a given, since the professors would be the ones to know best. However, I had a few classmates that were more inclined to question what we were taught, and we soon became friends. Two of these classmates were from Nazarene backgrounds, and two were from Charismatic backgrounds, and were attending a Vineyard Church (which was sort of a non-denominational denomination which had services that were very laid back, and music that was very much “Top-40” worship (rock band, “worship team”, etc). It was the “Un-Church”. People would kick up their feet, and pop open a coke. With rare exceptions, you would not see a suit and tie… but jeans, t-shirts, Bermuda shorts, and Hawaiian shirts. They were focused on spiritual gifts, spiritual warfare, casting out demons, healing the sick, and prophecy. I found a lot of it very attractive, but I was never able to bring myself to join it. There were elements of their doctrine that I could not accept. For example they believed in eternal security (“once saved, always saved”), and Nazarenes decidedly did not. Also, my previous experience with Pentecostalism left me a little more skeptical of some of the excesses that I saw.

While at school, my studies went on several tracks at once: there was the material I had to read for class; there was the material I read to counter the material I had to read for class; there was the material I read because I became interested in a particular topic; and then there was the material I read because I was looking for something deeper. The third and fourth tracks evolved over time. In the first year or so, I was especially focused on digging deeper into the Holiness Movement that the Nazarene Church was a part of. I read Charles Finney’s works, almost completely. I also read many other Holiness writers… John Wesley, of course; William and Catherine Booth, founders of the Salvation Army (which is a denomination, not just a charity); Hannah Whitall Smith; Samuel Logan Brengle; Phineas F. Bresee; “Uncle” Bud Robinson; A.M. Hills; H. Orton Wiley; Watchman Nee; and many other lesser known writers. I also studied the history of Methodism, and the Holiness Movement extensively, as well as the connection between those movements and Pentecostalism. I had hoped that by digging into the roots of the Holiness tradition, I could discover what was now missing in it. I did find many admirable historical figures, and found their devotion to God and the seriousness with which they approached the spiritual life to be impressive. The descriptions of the old revivals made me think that maybe they had something back then that had been lost along the way.

The Pentecostal movement was originally an offshoot of the Holiness Movement… in fact the birthplace of Pentecostalism is generally considered to be the Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles, which was founded by a black Nazarene pastor who had started preaching that you had to speak in tongues to be filled with the Holy Spirit, and was soon thereafter locked out of his Church by his congregation. At that time the Nazarene Church was actually known as the “Pentecostal Church of the Nazarene”… but the term “Pentecostal” was previously used in reference to the “second blessing”, which was the work of “entire sanctification”, which was taught to be the result of the Baptism of the Holy Spirit… which was generally believed to happen at some point after justification, i.e., when someone comes to a “saving faith” in Christ. I discovered that the Pentecostal movement had in fact hijacked a number of terms (such as “Full Gospel”) that had been common in the Holiness Movement, but because the mainstream Holiness Movement was so anxious to distance themselves from the “tongue talkers”, they quickly abandoned terminology that might associate them with this new movement, and in the process they also moved away from much of the revivalist spirit that had characterized them. The Holiness Movement is actually where the term “Holy Roller” came from… because people used to roll in the aisle, jump pews, run around the Church, climb poles, shout, wave their hankies, etc. I worked for an old man whose father had been an old time Nazarene Evangelist, and he told me that when he was a kid, tour buses from Oklahoma City use to take people to Bethany First Church of the Nazarene, so that they could see these kinds of things for themselves. You wouldn’t know that from the Bethany First Church of the Nazarene of the time that I was going to school, or pretty much any other Nazarene Church. So I began to wonder if maybe the fervor of the Holiness Movement had been lost due to an overreaction to Pentecostalism, and so I began to see if I could find something that was somewhere in between what the Nazarene Church was that I had known, and the Pentecostal movement, which I knew had a wacky side to it, that I wanted to avoid.

In the summer of 1988 my wife and I were married in the Chinese Baptist Church that she had been attending in Houston. Due to the efforts of my very frugal wife, we were able to have a nice wedding, a reception, a honeymoon, and to move her stuff to Oklahoma, all for about $1,000.00. That following school year, I thought I had found what I was looking for. There was a non-denominational Church that had been started in the Bethany area, which consisted mostly of former Nazarenes with charismatic tendencies, and the pastor had been a Nazarene music evangelist (he and his wife would sing at revivals around the country). He was even a graduate of Nazarene Theological Seminary, but I discovered that while he was a nice and sincere man, he was not very theologically inclined. In fact, when I began attending there, he asked me to take over their adult Sunday School class, and also to write up a doctrinal statement for their Church. He had started a study of the book of Hebrews, and so I continued where he had left off, and enjoyed digging into the book of Hebrews and laying out what it meant for the class.

I also took up the challenge to write a doctrinal statement, and using the Nazarene Articles of Faith as the starting point (which were printed in what is known as “The Nazarene Manual”, which originated out of the Methodist Book of Discipline, and was sort of a doctrinal statement of the denomination, combined with the rules that govern the Nazarene Church on its various levels, and also provided standards of Christian behavior that Nazarenes were expected to adhere to), supplementing that with a few things from the Salvation Army Handbook of Doctrine (which is similar in scope), and throwing in a few things about the gifts of the Holy Spirit, I came up with a text, and presented it to the pastor. His reaction was “Man… this is so negative! There’s all this stuff about sin! It sounds like the Nazarene Manual!” I responded that it was in fact based on the Nazarene Manual’s Articles of Faith, and then we began discussing the question of whether doctrine should be rooted in anything from the past. He told me “God has a “Now” word for the Church,” and that basically we didn’t need to worry about what a bunch of dead people thought about doctrine. I asked him whether he thought God had spoken through men like John Wesley. He said that he believed He had. So I asked, if God did speak through men like John Wesley, wouldn’t that message be something that we would want to know and understand? He didn’t have a satisfying answer. But that text did not become the doctrinal statement of that Church… nor did anything else. I noticed over time that this pastor would preach based on whatever he happened to be reading at the time. For a while he was preaching sermons based on a Christian novel about spiritual warfare entitled “This Present Darkness.” Then he started preaching from Watchman Nee’s book “Spiritual Authority.” It began to seem like that church’s doctrine hinged on what he had eaten the night before. I increasingly began to see the folly of non-denominational Churches that have no accountability to anyone or anything beyond the whim of the pastors who head them.

Things came to a head one Sunday when, because I was teaching on the book of Hebrews, I taught about the question of whether or not one could lose their salvation (an issue raised by Hebrews 6:4-6 and Hebrews 10:26-27). I had no reason to think that this was going to be a controversial issue, because Nazarenes believe that you can lose your salvation. However a number of the people who had joined this church were from a Southern Baptist background, where “Eternal Security” is the prevailing doctrine. While I was teaching this class, there was one guy I had not seen before who kept arguing with the points that I was making, but I thought I was batting his objections out of the park pretty handily. Then after the class, I had a women from a Baptist background, who was so upset that she was shaking. She had never heard eternal security challenged before, and didn’t know how anyone could believe anyone could be saved, if eternal security were not true. I tried my best to calm her down. Then the main service began, and as it turned out, the guest speaker that Sunday was the guy who had been taking shots at me in the class. During the sermon, the tables were turned, but unlike a Sunday school class, it is not generally accepted behavior to challenge a man giving a sermon during the service. He didn’t call me out by name in that sermon, but anyone in the class knew who he was talking about. After the service, the pastor called me aside, because he had heard that some people were upset by what I said in the Sunday School class. He told me that I needed to “get off of that doctrine stuff”, because doctrine “divides”. I pointed out to him that he was the one who had picked the book of Hebrews to study, and asked him what I was supposed to do when I came to passages that clearly taught that salvation was not guaranteed, just because you had once made a profession of faith. Again, I didn’t get a good answer, and that was my last Sunday at that Church. I soon went back to one of the new Nazarene churches in the area, and from that point forward had a new appreciation for doctrine, Church authority, and Tradition.

The new Nazarene Church, that I began attending seemed like the ideal I had been looking for. It was started by the initiative of the District Superintendent (who functions a bit like a diocesan bishop) with the intention of attracting people who we inclined to a more “charismatic” environment. It didn’t even have “Nazarene” in its name – it was called simply “The Sonlight Center” – although this had previously been a requirement for every local Nazarene Church. It had a rock band, “Top 40” worship, and an emphasis on the gifts of the Spirit – but it also already had a doctrinal statement, and was accountable to a wider church. Eventually I became the associate pastor of this church.

One of the ministries that this church began to get involved in was pro-life activism. In fact, this church started the local chapter of “Operation Rescue”, which was leading protests at abortion clinics, and whose favorite tactic was to blockade the entrance, using the methods of passive resistance which had been used by the civil rights movement, and try to shut the clinic down for as long as possible. At the first meeting we held, Fr. Anthony Nelson of St. Benedict Orthodox Church arrived in his riassa and pectoral cross, and I turned to my wife and said facetiously, “Can you imagine me dressed like that?” After the meeting, one of the ladies in the Church informed me that they had intended to send an invitation to every church in the Oklahoma City area, but that she didn’t have sufficient postage, and so prayed that God would guide her in selecting which churches to send the invitations to. So the fact that Fr. Anthony even got the invitation, not to mention that he came, was an unlikely event to have happened, but one that proved to be crucial in my journey to the Orthodox Church.

There were several things that I studied in depth that began to open my eyes to the fundamental flaws in Protestantism, and also to the importance of Tradition: Textual Criticism, Empiricism and its role in Protestant Biblical Scholarship, the question of the inspiration of Scripture, the works of Thomas Oden, books about Orthodoxy, and then the writings of the Fathers themselves.

I began studying the question of textual criticism as a result of studying New Testament Greek, and becoming aware of textual variations. I read several books by John Burgon, who was an Anglican scholar of the 19th Century, who was born in Smyrna, and so grew up speaking Greek. He was an authority on Patristics, and wrote extensively against the work of Wescott and Hort – two Anglican scholars that popularized the approach to textual criticism that is reflected in the Greek text used by most modern Protestant translations, with the exception of the New King James Version, and a few other lesser known versions (and of course in the case of the King James Version, it was based on the Textus Receptus which essentially is the same as the text in most Greek Manuscripts, having predated Wescott and Hort by a few centuries). I also read other more contemporary authors on the subject, such as Zane C. Hodges and Wilbur Pickering, and read debates in which Hodges and Pickering, advocates of what is now known as “The Majority Text” or the “Byzantine Text”, debated those advocating for the Wescott-Hort approach. This is a complicated subject, and it is too big of a topic to get into any depth here, but suffice it to say that I found the arguments in favor of the traditional Greek text more compelling, and those arguments depend in large part on a belief that God has preserved the textual tradition of the Church… which if you accept that, raises the broader question of the reliability of Tradition.

In a graduate level course I was taking on Scripture (which was tag-team taught by the two most liberal professors that I had), I chose to do a paper on the role of Positivism in Biblical scholarship. This is also a complex issue (though I go into some detail on it in my essay on Sola Scriptura) but I began to see the rationalism that is at the heart of Protestantism and has been since the days of Martin Luther and John Calvin.

In that same course, our final paper, which we were each in turn to present to the class in the final days of the semester, was to be an exposition of our personal theology of the inspiration of Scripture. I had noticed from the beginning of the semester that it seemed as if the entire purpose of that class was to convince the student that the Bible was full or errors, but to somehow also affirm that it was nevertheless inspired. I decided to actually put the “Wesleyan Quadrilateral” to work, and so analyzed the question by first asking what Scripture says about itself, then what Tradition says about the nature of Scripture, and then look at the question from the perspective of reason and experience.

You wouldn’t know it from attending most Nazarene Churches, but because the Nazarenes historically traced their roots through the Methodist movement to John Wesley, they have a remote connection with Anglican Tradition. I had some idea of that growing up in it, and reading Nazarene publications… in fact as a teenager, I actually fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays for about a year, because I had read that John Wesley fasted on these days, based on the practice of the “Early Church”. But if you didn’t notice it as a laymen, you certainly get introduced to these Anglican roots when you study to be a Nazarene Minister. In Anglican theology, they have the concept of the three-legged stool of Anglicanism: their theology is based on Scripture, Tradition, and Reason. John Wesley added one more leg to the stool (Experience), and so the “Wesleyan Quadrilateral” was born. The basic idea is that Wesleyan Theology is supposed to be based primarily on Scripture, but Scripture interpreted by Tradition, Reason, and Experience – in that order of importance. In actual practice, however, you rarely heard any talk of Tradition outside of discussions of the doctrine of the Trinity, or Christology.

Most of my research on the question of the inspiration of Scripture focused on the question of what Tradition had to say about it, and since at that point I had more or less a “branch-theory” understanding of what constituted the Church, I analyzed it in terms of what the “Early Church” had taught on the question, then what the Roman Catholic Church, Orthodox Church, and then the various major branches of Protestantism had historically taught… with a special emphasis on the branch that I was on at the time. What I found was that all Christians had affirmed the idea that the Scriptures were fully inspired, and were in fact inerrant. I had good sources for most of those sections, but not for the Orthodox. But I knew enough about the Orthodox Church to know that I needed to adequately cover their perspective. Since I had met Fr. Anthony Nelson and worked with him on several protests, I decided to call him up and discuss it with him. When he explained the Orthodox understanding of the inerrancy of Scripture, it made so much sense that it essentially became the final conclusion of my paper. In short, his explanation was similar to the one I later found in the writings of St. Augustine (Letter to St. Jerome, 1:3). We believe that the Scriptures are inerrant because God, as the one who inspired them, is on one level the author. If, however, we find something in Scripture that seems at odds with reason, we conclude that either we have flawed reasoning, or we have misunderstood the meaning of the Scriptures, or perhaps we have a bad translation or a bad manuscript… but we know the Scriptures are true… and if we don’t know for sure which of the above factors is the cause for the apparent conflict with reason, we don’t spend too much time worrying about it, because our understanding of the Scriptures as individuals is not infallible, nor should we expect it to be. The Church’s understanding of the Scriptures as a whole is infallible, and if we remain under the guidance of the Church, we will not go too far wrong.

As St. Gregory the Theologian wrote:

When the day came that I presented my paper to the class, I presented the view which the Church had always held regarding the Scriptures, and made the case that if the Church has always taught something, it must be true, because it was not possible for the whole Church to affirm something that was in fact erroneous. The same professor that had lectured about tearing down the walls around our faith (at the beginning of my studies at SNU) was the one that most vocally challenged my thesis. At one point he made the statement that if I was going to argue that position, I would have to “become a Catholic, accept the Apocrypha, the Pope, and Purgatory”. I responded that if I could be convinced that the Church had always taught those things, I would accept them… but that I didn’t think that was the case [the Orthodox do accept the Deuterocanonical Books, but not the notions of the Papacy, or Purgatory].

At this point I had no idea that I would be making any radical shifts in my Church affiliation, but I did believe that I had discovered a new theological method, which could settle pretty much any theological controversy. No matter the question, one needed only to ask “What has the Church always taught on the matter?” Once you found the answer, the problem was solved; you just needed to conform to the teachings of the Church. And to be clear, at this point my idea of the Church was based on the branch theory of the Church, but even if you see the Church as a tree with branches, you still end up with the same trunk.

However, when I began to seriously study the writings of the Methodist theologian Thomas Oden, I realized that my new theological method wasn’t a new method at all – it was only new to me. Much of the material I was assigned to read while at SNU was a labor to be endured, nothing inspiring or edifying – but there were a few exceptions, and prominent among those exceptions were the books by Thomas Oden. Oden had been a student of the extremely liberal German biblical scholar Rudolph Bultmann, and so was very much a part of the skeptical intellectual environment that I found so unattractive. However, at some point in the 70’s he began to apply the skeptical criteria of liberal scholarship back upon liberal scholarship, and ended up affirming the idea that the “Ecumenical Consensus” of the first millennium of Christian history was “normative”. I was introduced to his work in my Systematic Theology class. He had at that time written the first two volumes of a systematic theology that followed the outline of the Nicene Creed, and was in many ways an introduction to the Fathers, and an index to point you to where in their writings you could find what they had to say on the questions covered by the texts. In that class, we used volume 2, “The Word of Life“, which focused on those parts of the Creed that related to Christ. That book was so refreshing that I got me a copy of volume 1, “The Living God“, and read it as well. I also found that our library had his book “Agenda for Theology“, which was I think then out of print, but was his theological manifesto, and explained how he had moved from being a Bultmannian to one who affirmed the authority of the Tradition of the Church. That book was later reprinted in a significantly revised form, under the title “After Modernity… What?” In one of my Pastoral Theology classes, they also used his “Pastoral Theology” as a textbook, which went to the Tradition of the Church for guidance on how to deal with the practical issues of pastoral theology.

There was one chapter of “The Word of Life” (chapter 7, which dealt with the question of the “Quest for the Historical Jesus”) that was such a thorough critique of Protestant liberalism that I put Batman comic sound effects in the margin: “Boom!”, “Pow!”, “Smack!”, etc.

The third volume of his “Systematic Theology” was not published until 1992, and by that time I had been Orthodox awhile, and so was less eager to purchase a copy, though I always had the intention of eventually doing so, in order to complete the set. Twenty-two years later, I finally got around to it, and reading it was a walk down memory lane. Reading the preface freshly reminded me of what a radically different spirit I found in his writings in comparison with most of the material I had studied at SNU.

In the second paragraph of his preface, he wrote:

“At the end of this journey I reaffirm solemn commitments made at its beginning:

• To make no new contribution to theology

• To resist the temptation to quote modern writers less schooled in the whole counsel of God than the best ancient classic exegetes

• To seek quite simply to express the one mind of the believing church that has been ever attentive to the apostolic teaching to which consent has been given by Christian believers everywhere, always, and by all – this what I mean by the Vincentian method (Vincent of Lerins, comm., LCC [Library of Christian Classics] VII, pp. 37-39,65-74; for an accounting of this method see LG [The Living God (volume 1 of his systematic theology)], pp. 322-25,341-51)

I am dedicated to unoriginality. I am pledged to irrelevance if relevance means indebtedness to corrupt modernity. What is deemed relevant in theology is likely to be moldy in a few days. I take to heart Paul’s admonition: “But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel other than the one we preached to you, let him be eternally condemned! As we [from the earliest apostolic kerygma] had already said, so now I say again: If anybody is preaching to you a gospel other than what you accepted [par o parelabete, other than what you received from the apostles], let him be eternally condemned [anathema esto]!” (Gal. 1:8, 9, NIV, italics added) (Life in the Spirit, Systematic Theology Volume Three, (New York: Harper & Row, 1992) p vii).

I can’t remember in which of his books he said this, but I remember him echoing the above sentiments, and saying that he wanted the epitaph on his tombstone to say: “He added nothing new to theology.”

Thomas Oden is still a Protestant, and so one should not assume that I would agree with him entirely, but his devastating critique of Protestant liberalism and modernity in general, combined with his affirmation of the Tradition of the Church was an oasis in a spiritual and intellectual desert.

Around the time I began digging into Oden’s “Systematic Theology,” I received 2 books that Fr. Anthony Nelson had suggested I read if I wanted to understand more about the Orthodox Church: “Orthodox Dogmatic Theology”, by Fr. Michael Pomazansky, and “Becoming Orthodox”, by Fr. Peter Gillquist. I was struck by many of the parallels between “Orthodox Dogmatic Theology “and what I was reading in Oden’s books, but I was also struck by some of the differences. I often wrote notes in the margins, and in that book I wrote comments like “No way!” out to the side, but after becoming Orthodox I had to go back and scratch those comments out. “Way!”

“Becoming Orthodox” was also an eye opener. I had heard about the “Evangelical Orthodox” and their journey from Campus Crusade for Christ to the Orthodox Church. A guest lecturer mentioned it… and I don’t remember why he mentioned it, but I remember the puzzled look on the faces of those who heard it… which no doubt mirrored my own expression. I think there was even some audible responses to it, like “Huh?” or “What?” My own reaction was to wonder what they could possibly be thinking. Reading the book answered my question. It did not convert me, but I think the main thing that was accomplished by reading that book was I saw that converting to Orthodoxy was a real option, though at that time I still didn’t consider it a very serious option.

I also began reading the Fathers themselves, not just reading about them, with the occasional quotation one might encounter. Coming from Protestant assumptions, the earlier the Father was, the more trustworthy he was likely to be. One of the earliest Fathers to be found outside of the New Testament is St. Ignatius of Antioch. He was a disciple of the Apostle John, was consecrated Bishop of Antioch by St. John himself, and martyred in the arena of Rome in 112 A.D. So I read his seven epistles with great interest, and was again and again struck by the fact that he was not a Protestant:

“Similarly, let everyone respect the deacons as Jesus Christ, just as they should respect the bishop, who is a model of the Father, and the presbyters as God’s council and as the band of the Apostles. Without these no group can be called a church” (Trallians 3:13).

“Make no mistake brethren, no one who follows another into a schism will inherit the Kingdom of God, no one who follows heretical doctrines is on the side of the passion” (Philadelphians 3:3).

“Be zealous, then, in the observance of one Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one chalice that brings union in His blood. There is one altar, as there is one bishop, with the priest and the deacons, who are my fellow workers” (Philadelphians 4:1).

“But consider those who are of a different opinion with respect to the grace of Christ which has come unto us, how they oppose the will of God…. They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness raised up again. Those, therefore, who speak against the gift of God, incur death in the midst of their disputes. But it were better for them to treat it with respect, that they also might rise again” (Smyrneaens 6:2-7:1).

“Flee from divisions, as the beginning of evils. You must all follow the bishop, as Jesus Christ followed the Father, and follow the presbyters as you would the apostles; and respect the deacons as the commandment of God. Let no one do anything that has to do with the Church without the bishop. Only that Eucharist which is under the authority of the bishop (or whomever he himself designates) is to be considered valid. Wherever the bishop appears, there let the congregation be; just as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not permissible either to baptize or to hold a love feast without the bishop. But whatever he approves is also pleasing to God, in order that everything you may do may be trustworthy and valid” (Smyrneans 8:1-2).

“Assemble yourselves together in common, every one of you severally, man by man, in grace, in one faith and one Jesus Christ, who after the flesh was of David’s race, who is Son of Man and Son of God, to the end that ye may obey the bishop and presbytery without distraction of mind; breaking one bread, which is the medicine of immortality and the antidote that we should not die but live for ever in Jesus Christ. (Ephesians 20:2).

Here we had a disciple of the Apostle John, teaching that the Eucharist was truly the body and blood of Christ, that it was the medicine of immortality, that it could be valid or invalid, depending on the authority of the bishop, that no group that did not have bishops, priests and deacons could be called a church, and that no one who went into schism or heresy would inherit the Kingdom of God. When I read these epistles for the first time, I was not sure where I would end up, but I knew I could no longer remain a Protestant. For about 10 seconds, the thought of Anglicanism occurred to me, and had I been born a hundred years earlier, I might have settled for the option, but the doctrinal decay of the Anglican Church had reached such a point by that time, that I could not consider it a serious option.

In one of my practical theology courses (I think it was entitled “Theology of Christian Worship”) one of our assignments was to visit a certain number of worship services that were not the typical Evangelical Protestant services that we were used to. I used this as an opportunity to go to a service at Fr. Anthony Nelson’s parish. It was a Saturday evening Vespers, and though St. Benedict has a very beautiful Church building today, it didn’t in January of 1990. They were in a storefront that was small. The ceiling tiles had visible rust stains from past leaks. The carpet looked like it had seen better days. The congregation was not large. However, the singing was well done, and I had a sense that this was the real thing when it came to worship. In fact, I noticed elements that reminded me of things I had read about Synagogue worship, and so could see that this kind of worship had to have very ancient roots. And the Saturday evening Prokimenon, sung in Znamenny Chant, “The Lord is King, He is clothed with majesty” (Psalm 92:1 lxx) struck me particularly. I later read about how the envoys of St. Vladimir reported back about a service they attended in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, “We didn’t know whether we were in heaven or on earth.” I was not in the Hagia Sophia by any stretch, but I had a similar experience.

My interest in Orthodoxy began as an academic curiosity, but gradually it developed into something else. At first I just thought it would be beneficial to know more about it. Then I thought that there are a lot of cool things about it, but I still couldn’t see myself accepting it. Then, over time, I began to think that I could become Orthodox, if only I could answer about five questions (the veneration of Icons; the ever-virginity of the Virgin Mary; the veneration of the saints; praying to the saints; and prayers for the dead), but I didn’t think it likely. Then I began to study each of those five questions, and gradually they were answered, one by one. I would research the question of the moment, look through the earliest writings of the Fathers on that subject, and in each case was eventually satisfied that each of these Orthodox beliefs were consistent with the earliest Traditions of the Church. And light bulbs would go off in unexpected ways. For example, one day I was talking to a neighbor who was talking about the wife of a retired professor at SNU. He said that this woman was such a woman of prayer that if you ever needed an answer to prayer, she would be the one to go to, because she “had a hotline to God.” Having known some very pious Nazarenes over the years, I didn’t find his account hard to believe. But then it dawned on me, if any woman ever had a hotline to God, that would be first and foremost, the Virgin Mary, wouldn’t it? And didn’t Christ say that God was the God of the living and not the dead (Matthew 22:23-33), and so if I could ask this pious old Nazarene woman from Bethany, Oklahoma to pray for me, couldn’t I also ask the Virgin Mary from Nazareth of Galilee to pray for me?

Furthermore, when you come to understand what the Church is, you reach a point at which you trust the Church without needing further proof. From reading the writings of St. Cyprian of Carthage (who reposed in 258 A.D.), I learned that it was not possible that the whole Church could teach as true that which is erroneous (see especially his Treatise on the Unity of the Church).

So after all my research and study, I was fairly certain that I wanted to become Orthodox, and so I decided that it was time to fill my wife in on it – according to a journal that I was keeping at the time, I reached this point on about April 28, 1990 (which was just about a month before I graduated from SNU). This came as quite a shock to her. I had not talked to her, or anyone else except Fr. Anthony Nelson and Anna Voellmecke (his choir director). The reason was simple. I figured that if anyone thought that I was contemplating such a radical shift, that they would question my stability (maybe even my sanity)… and if I became convinced that this was the right way to go, I was prepared to suffer whatever consequences that decision might bring. However, until I was sure that I wanted to do that, I didn’t let even my wife and closest friends know how serious my interest in Orthodoxy really was. Unfortunately, this had the effect of leaving many of my classmates and acquaintances thinking that one day I was a conservative Nazarene, and then on a whim I one day became Orthodox, but in reality it was the conclusion of a very long process and a great deal of intense study.

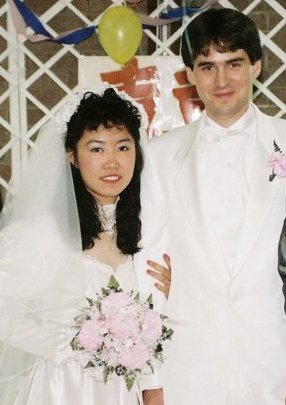

My wife and me, on our wedding day

May 28, 1988

As my doubts about Protestantism increased, I found myself in a very unpleasant situation. As an associate pastor, I had certain responsibilities, which included leading a small group on Sunday nights, and also occasionally preaching on Sunday morning. I continued to fulfill these duties, but was increasingly less convinced about the things that I was expected to teach and preach. I also began attending Saturday night vespers at St. Benedict on a regular basis, and then on Sunday morning, I was back at the semi-charismatic Nazarene Church of which I was the associate pastor. The contrast between these two very different styles of worship on a weekly basis had the effect of increasingly convincing me of the shallowness of Protestant worship in general, but especially the “contemporary” style of worship that my Nazarene Church was using. There were two “worship songs” that stood out as being especially shallow. One was “As David did in Jehovah’s sight, I will dance with all my might” – which had no meaning other than that we were going to jam to the tunes of the rock band that was playing the music. Another was “Blow the Trumpet in Zion,” which was based on words from Joel, chapter 2. However, this song twisted the meaning of the words in that prophecy to suggest that it was talking about what a powerful army the people of God were, when in fact the prophecy is a prophecy of judgment on the people of God who have sinned. The army that is talked about in that passage, that is about to “run on the city” and “run on the walls” is an army that is coming to destroy Zion (Jerusalem) at God’s command. The trumpet is blown in Zion to sound the alarm, because Jerusalem is under attack. God is calling His people to repent, if they wish to avoid this judgment… but this “contemporary worship” song is anything but a penitential song. One Sunday, when I was asked to preach, I preached on Joel 2, and explained why this song distorted the meaning of the passage, and what it actually meant. Next Sunday, the “worship team” sang it again, as usual.

The Sonlight Center had met with moderate success in building up a congregation, but it was initially underwritten by the District (which is similar to a Diocese), and had a very expensive lease on a very nice and large storefront facility, but the District only promised to provide financial backing for a period of about a year, and the day came when that support ended. I was not much involved in the business side of that Church, but a decision was made that we needed to look for a new and more affordable location. While we were in transition, our services were for a time held at a Messianic Jewish Church, which obviously would not have services on Sunday, since it had its services on Saturday. But since they were hosting us, I attended some of their services. Their services bore almost no resemblance to a traditional Jewish Synagogue service. Essentially, their worship was typical Charismatic worship, with some cheesy Jewish stuff thrown in, and a lot of Fiddler-on-the-Roof style music. I found that the people in the Church were almost all Southern Baptist Okies that were looking for something that had tradition. I thought it was unfortunate that instead of looking into Christian Tradition, they had gone down the path of Judaizing Christianity. This was just further evidence of the collapse of Evangelicalism, which has only accelerated in the years since.

Things finally reached the point where I was more than ready to convert, and my wife was also comfortable enough with the idea of attending St. Benedicts, that I was ready to make a final break with the church I had been raised in. On June 29th, 1990, I informed the head pastor of my Church that I would be leaving the Church of the Nazarene. I didn’t tell him where I was going to go, because I knew his church was in a shaky financial state, and I thought that if the average person in that Church knew why I left, it might cause him problems, and I didn’t want to be the cause of that Church finally folding. I am not sure, in retrospect if this was the best plan, but I knew most of the people in that Church would not be able to understand my decision, and I didn’t see the point in causing anyone to be scandalized. I figured I would tell those that I was close to later, including the head pastor… and I did several months later, but unfortunately, few of the friendships that I had in that Church survived my conversion.

My family also had a strong reaction. For example, when I informed my mother about my conversion, she seemed to take it pretty well, but then called me back about an hour later, and told me that I was going to hell. She did later apologize, but was vocally critical of my decision for many years thereafter.

I should point out that I did not leave the Church of the Nazarene angry. I was grateful for all that I had learned that was good and true, and the many sincere and loving people I had encountered. At the time I left, I thought of the Church of the Nazarene as a conservative denomination with many good qualities, but after discovering the patristic view of what constituted the Church, I simply became convinced that, as well meaning as it was, it just wasn’t the Church of the Fathers.

Had I never attended SNU, or had my professors at SNU been more in the tradition of the Holiness movement, I probably would not have been pressed to ask the kind of questions that led to my becoming Orthodox. I had several of the same professors that my older brother had when he attended SNU earlier in the 80’s, but the liberal professors that my brother had, were the conservative professors that I had, and they hadn’t become more conservative in the process. The older conservatives had mostly retired, and were replaced by professors who were even more liberal than the previous liberals had been. All of that is of course relative to the Church of the Nazarene which was a fairly conservative Evangelical denomination in those days (James Dobson being one of the most prominent examples of a Nazarene in America). Later, after I graduated from SNU (and had converted to Orthodoxy), I had the chance to attend Phillips Theological Seminary with a full scholarship. However, because it was then located in Enid, Oklahoma (which is not near a major city, in which employment would be more easily obtained), I decided to dip my toe in the water and take a satellite course that they taught in Oklahoma City. That course was taught by a professor who made even the most liberal professor I had at SNU look like a fundamentalist by comparison… I am honestly not sure if he even believed in God, but in that class he certainly gave no evidence of any faith. The second half of my Sola Scriptura essay (“The Orthodox Approach to Truth”) was actually originally written as a 10 page preface to a paper written for this professor, which I wrote to explain why I was not going to approach the Scriptures in the way that his assignment called for. Unlike my professors at SNU, it became clear that disagreeing with his perspective was not welcomed, and so I made the decision that it would not be worth my time to spend four more years covering the same ground, but in an environment less opened to engaging ideas that were not part of the dominant liberal perspective of the school. So in retrospect, I came to see the liberal professors I had at SNU in a more charitable light. I suspect that they had been confronted with that sort of dry liberalism at some point in their education, became convinced that much of the scholarship was accurate, but still managed to reconcile it with their own faith, and sincerely wanted to help their students better prepare for the shocks that they were to face along the path of their academic studies. So while I never came to see things the way my professors did, I came to better appreciate many of the good things I had learned from them, and sincerely appreciate the fact that they made me ask the questions that led to my discovery of the Fathers of the Church.

Fr. Anthony Nelson invited my wife and me to tag along with him on a trip to Holy Trinity Monastery (the spiritual center of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR)), in Jordanville, New York, and the Synod Headquarters in New York City, and so we did. While in Jordanville, on July 24th (St. Olga’s day), I was made a catechumen. Fr. Anthony and I had talked about it, and my wife came to the point where she was OK with it. So Fr. Anthony asked for, and received permission to do the service in the monastery cathedral. Being made a catechumen has many similarities with the betrothal service, and this is intentional, because a catechumen is sort of betrothing himself to the Church. The commitment is made; however, the relationship is not yet consummated – but like a betrothal, it is a very big step.

Seeing upstate New York was a surprise to me. I had expected all of New York to be a rusted urban jungle, but upstate New York was very beautiful… nothing like the stereotypes I had in my mind. From Jordanville, we traveled to New York City, and in the pre-Giuliani days, graffiti was everywhere, and I saw where all those stereotypes about New York had come from. But when we arrived at Synod, it looked like a very nice part of New York, City. We went in, and there I got to meet for the first time the very kind and loving Metropolitan Hilarion, who was then the Bishop of Manhattan. After about an hour, we came back outside, and discovered that in broad daylight, our van had a window smashed out of it, and much of our luggage had been stolen. Among the things that I lost was the Bible I had purchased as a Freshman, and had marked up, and so familiarized myself with that I knew what part of a page to look at to find a particular text. In some ways, this was another connection with my Protestant past that had been broken. On our way out of New York City, we were told by a guy at a gas station, who saw the broken glass and had been told about our stolen luggage, “That’s what you get for parking in the city with out of state plates.”

Because I had come so far studying Orthodoxy on my own before I had filled my wife in on it, she had a lot of catching up to do. She was not closed minded on the subject of Orthodoxy, but she was also not going to convert just because it would make me happy. Over the years I have known people who assume that Asian women are all like the obedient and submissive Japanese wives they have seen in the movies. I have not gotten to know many Japanese women, but I have gotten to know many Chinese women, and they are not that way. I once worked as a waiter in a Chinese restaurant, and the owner’s wife, who was about five feet tall, and relatively thin, seriously offered to protect me when I had to deal with some rowdy customers (and I was at the time 6’2”, 190 lbs., and had been studying martial arts for 2 years). So I was under no illusions that my wife was going to convert for any reasons other than her own. I had hoped that I might be able to convince her over time with the arguments that had convinced me, but as the fall of 1990 began, I began to think that she might never convert. My wife said that on the day of judgment she would be the one who would have to answer for her decision, not me… and I could not argue with that.

My wife’s decision to convert or not to convert was a question that would decide whether or not I could eventually pursue becoming an Orthodox priest, because an Orthodox priest cannot be married to a non-Orthodox woman. The wife of an Orthodox priest is one flesh with her husband, and so has a share in the priesthood. The canonical requirements to be a priest’s wife are pretty much the same as they are to be a priest, aside from the question of one’s sex. The priest’s wife even has a similar title. In Greek custom, the priest’s wife is called “Presbytera” which is the feminine form of “Presbyter” (the Greek word for “Priest”). Arabs call a priest “Khoury” (which means “Priest”), and his wife “Khouriah” (again, the feminine form for Priest). Russians call a priest “Batiushka” (literally “little father”), and his wife is called “Matushka” (“little mother”). The Matushka of a parish has no liturgical role in a parish, but she does have a motherly role, and so this is why a priest cannot be married to someone who is not Orthodox. So faced with the likelihood that my wife’s decision to not convert would eliminate the possibility of becoming a Priest, I had to consider what else I might do with my life.

As it happened, the first Gulf War was on the horizon, and so I decided to join the military, for two reasons: 1) because, as the son of a World War II veteran, I felt like it was my turn; and 2) because if I couldn’t be a clergyman, I thought the next best thing would be to be a United States Marine. No one knew beforehand that the war would be brief, and as one sided as it turned out to be. The media played up the strength and size of the Iraqi army, and many predicted that we would end up in a quagmire that would go one for many years. I was sworn in (in the same building that Timothy McVeigh would later blow up) in early November of 1990.

I had moved slowly up to this point, hoping to be baptized with my wife, but she was comfortable with my being baptized after I enlisted, because she knew I would shortly be going to boot camp, and would possibly be in a war soon thereafter. And so on November 10th, 1990, I was at long last baptized. It was a great joy to be able to fully participate in the services, and to receive communion for the first time on the following day. I prayed that my wife would eventually follow me, but I decided that I would only answer questions she asked, and not say anything that might seem like I was pushing her any further on the subject.

I had spent a great deal of time praying about my decision to enlist, and had spent a good bit of time getting advice on it, and thinking about it. But at the time, it seemed like the right thing to do, and I hoped that this was God’s will, but one of the things I had learned from the writings of Charles Finney was that it was a good idea to pray that God would thwart whatever you were doing, if it was not His will. So I prayed regularly that if it was not God’s will that I become a Marine, that He would not let it happen. While I was waiting to ship to boot camp, every month I had to attend a “poolee meeting.” In January of 1991, the air war phase of the war was well underway, and a patriotic fervor was sweeping the nation. All the poolees gathered at the Marine recruiting station, and then we ran in formation to a nearby park. As we ran, with flags flying, people stopped to clap, to applaud, cars approvingly honked their horns. Once at the park, we exercised, got a taste of what our drill instructors would be dishing out at boot camp, and then played flag football. I had just finished college, and so was a bit older than most of the other guys, who were right out of high school. Many of them seemed intent on impressing their recruiters, and so were playing flag football more like regular football, but without the helmet and the pads. At one point, someone hit me from behind and I felt a slight pop in my lower back. At the time, I didn’t think much of it, but by the time we ran back to the recruiting station, I was in a lot of pain. I didn’t know it at the time, but God had answered my prayer.

The next day I could not sit, walk, or stand up without intense pain, and it wasn’t all that much better when I was lying down. I didn’t have health insurance – while in college I was supposed to have had it, but simply put on my forms that my insurance was covered by “YHWH, Inc”, and my policy number was “MT0817” (which was a reference to Matthew 8:17 “that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by Isaiah the prophet, saying: “He Himself took our infirmities and bore our sicknesses”). And although I had been sworn in, I was not active duty military (because I had not gone to boot camp yet) and so had no health benefits there either. So all I could do was go to a general practitioner and pay out of pocket, and unfortunately, he never had any idea what the problem was. He thought it was a pulled muscle, and prescribed some anti-inflammatory medications, and some pain killers… doses of 500 milligrams of Ibuprofen. One day it occurred to me that I normally took more than that for a good headache, and so it was no wonder that it was of little use. Days went into weeks, and weeks went into months, and there was only mild improvement. My date to ship to boot camp, kept getting reset, and in the meantime, the war ended.

At one point my wife tried a Chinese remedy that involved putting an herbal plaster on my lower back, and then placing boiled dog skin over it, to keep it there. When it was time to remove it, I discovered that this remedy was not designed for Caucasians with a lot of body hair. I ended up having to shave it off, and howled like the dog whose skin I had stuck to my back.

Curiously, one thing that did bring some relief was doing lots of prostrations. I found that if I did at least 50 prostrations a day, I had less pain, but if I failed to do it, my pain increased

After a while, it seemed like the pain was becoming manageable, and I began to work on getting back into shape. But then while working out one day, I felt another pop, and then I was back to square one. Soon thereafter, I came to the conclusion that I was not going to be able to go to boot camp, and then, after having to get my congressman to press the question, I was finally able to get the Military to release me from my enlistment. It took about another year for my back problem to mostly go away (though it still gives me some grief to this day). When I finally did get health insurance years later, I was told that I had hyperextended a semi moveable joint in my lower back.

But all of this turned out to be providential. The change in the direction of my plans took the pressure off of my wife to make a decision. Also, my mother moved in with me that summer, and her continued efforts to talk me out of Orthodoxy helped talk my wife into it. And all the while, she had continued to attend services with me, and after the Service of the Twelve Passion Gospels of Holy Friday, 1991, she was so deeply moved, that she informed me that she wanted to be baptized. She was baptized on Bright Saturday, the following week, which was another unexpected answer to prayer.

Fortunately for us, Fr. Anthony Nelson had prepared us for the fact that converting to the Orthodox Faith was not the end of the road, but rather the end of the beginning of a long spiritual journey. You never reach the end of that journey in this life, but he especially impressed on us that it took a couple of years before one really began to think in an Orthodox manner. And so while I had been accustomed to teaching and preaching, I did not so much as teach a children’s Sunday School class until I had been Orthodox for 3 years. You could describe this process in terms of a worldview shift, or a paradigm shift.

A worldview is a set of mental paradigms with which we evaluate our experiences. Our worldview is the way that we think. It is the way that we look at things, process information; it is the paradigms in which we sort things through. Our worldview determines our expectations of reality, and our expectations largely determine our perception of reality. If we are faced with something that does not fit into our paradigm, then we are likely to be blind to it, or to try to make it fit artificially into our worldview. For example, in some cultures they only distinguish between two or three colors, bright and dark let’s say – so to such a person, blue and black are both just dark, the distinction is missed. Or for an example that is more close to home: what our culture’s predominant worldview would call an emotionally disturbed person, another (such as that of the Bible) might call demonized (which is of course not to suggest that all such cases would be). The expectations of these worldviews will either open or blind a person to certain possibilities. An animist would be blinded to the role that germs play in sickness, or that a head wound or brain damage might play in mental illness – an animist would see everything in terms of spiritual forces. A modern Empiricist, on the other hand, would be completely blind to the very possibility that spiritual forces could even play a part in such things as sickness or mental illness.

When people come to Orthodox Christianity from a heathen background (a person from an irreligious background, or from a religious background that is neither Christian, Jewish, or Moslem), in many ways they have an easier time accepting our Faith and practice without distorting it, because what they are embracing is so radically different from what they knew previously. They have a lot less to unlearn before they can properly learn the Orthodox Tradition, and they don’t think that they already understand words or concepts that they really don’t, in the proper Orthodox Christian sense.

When I was studying Martial Arts in High School, the style I studied was a form of Chinese Kung Fu. Now in my Martial Arts school we had a number of “converts” from Tae Kwon Do, who had for some reason decided that they wanted to learn Kung Fu. What was interesting though, is a neophyte could walk in off the street and they would have an easier time learning to do the forms and stances correctly. The problem was that many of the stances and forms, as well as punches and kicks were very similar – but just different enough to make it very difficult to learn to do it the Kung Fu way. But when it came time to put these techniques into practice – when we sparred – this problem became even more apparent. With time, many of these “converts” learned to do the stances and forms correctly (though the Tae Kwon Do influence could still be seen at times) but when they would spar – many of them would spar as if they had never studied Kung Fu at all. The instructor would often stop the action, and tell such people, “Look, Tae Kwon Do is fine, if you want to learn Tae Kwon Do, but you’re here to learn Kung Fu. If you want to learn Kung Fu, you’re going to have to put what you know about Tae Kwon Do aside and use the techniques that you’ve learned here.” The reason these people reverted back to Tae Kwon Do while sparring is simple – when you’re sparring, you’ve got to think and act fast, and Tae Kwon Do was what came natural to them – in fact it was preventing them from arriving at the point at which Kung Fu would become natural, and so until they could come to the point at which they would lay aside their Tae Kwon Do techniques – little progress in Kung Fu could possibly be made.

Similarly, in the Orthodox Church today there are many converts from Protestantism, who have seen in Orthodoxy that which they found lacking in their former Protestant experience, but very often they speak and act in very Protestant ways still. This doesn’t mean that a convert from Protestantism can never really become authentically Orthodox, but it does mean that he has some additional hurdles to overcome. I should also point out, however, that many “cradle” Orthodox who have grown up in America’s Protestant culture, often think in Protestant ways, and so many of them also have to go through a conversion process of sorts, if they are to acquire an authentically Orthodox mindset… and here, they can be even more disadvantaged than a former Protestant, because at least a former Protestant knows that he once was a Protestant. Too many of those born into Orthodox families are completely oblivious to the influence that Protestant thinking has had on them.

Former Protestants have the advantage of being more familiar with the Scriptures, and knowing much of Orthodox terminology, but often they do not move beyond their Protestant understanding of these things to an Orthodox one, or else they revert back to it at times in a pinch. A former heathen convert, doesn’t think he has already understood something that he has not – and so is more easily instructed. What I had to realize is that while I may have been a black belt Protestant, I was a white belt in the Orthodox Church, and so I had to learn the Faith from the beginning, and not assume that I already understood things.

This was not a comfortable transition. When people I knew would ask me about what the Church taught, if I knew for sure what the Church taught I would tell them. However, if they asked me about something that I was not sure of the Orthodox answer, I had to learn to give tentative answers: “I think the answer is such and such, but I am not sure. I’ll have to do some digging on that.” The constant question I had to ask myself was whether what I thought about something was really Orthodox, or whether this was simply my previous Protestant learning filling in the gaps. And I should say that after nearly 23 years in the Orthodox Church, I still at times find myself asking that question, and still have to give that same tentative answer, pending further study.

Obviously reading about Orthodox doctrine and Tradition is an important part of the process, though back when I converted there was a lot less available in English then there is today. Now, if you know which sites to go to, you can find a wealth of information with a few clicks of a mouse, but back then there were only the books that were in print (which you couldn’t generally find at your local library, and so had to purchase), and there were a number of Orthodox periodicals that I subscribed to. One thing that I found particularly helpful was reading the novels of Feodor Dostoyevsky. His novels conveyed the spirit of Orthodoxy in a way that a dry text about Orthodoxy generally cannot. But one body of Orthodox literature that inquirers into Orthodoxy and new converts often overlook is the reading of the lives of the Saints, and this is one of the most crucial things that we should devote our time and attention to. Bishop Peter (Loukianoff) says that St. John of Shanghai greatly stressed the importance of the lives of the saints, and often when asked a question about some matter of faith or practice, he would answer by citing something from these lives, which he had extensive knowledge of. And all the reading about Orthodoxy in the world will be of little help if you do not regularly attend the services, fast, pray, and live out the Orthodox Tradition in your daily life. St. Maximus the Confessor said “Theology without practice is the theology of the demons” [For more on this see the text of a talk I gave on this subject in 1995].

My wife and I stayed in Oklahoma until January of 1992, when I went to Jordanville with the intention of getting a job, getting housing that would be suitable, and then having my wife come to join me, and then I would attend Holy Trinity Seminary there. However, there is a Chinese proverb that says a wise rabbit has three holes, and so at that same time, my wife went back to Houston to get a job there, and we left most of our belongings in Oklahoma. Plan “B” was that if it did not work out in Jordanville, I would join my wife in Houston. We also had the option of returning to Oklahoma.

In Jordanville, I got to see the monastic life and live its rhythms, I learned a lot about the services, and I also experienced true culture shock for the first time – and it was a double whammy. In the monastery, I was surrounded by Russian and Slavonic. There was a lot about Russian culture and Orthodox etiquette that I had to learn. And then when I would travel to town, I was surrounded by Yankees. I was not much of a country music fan, but I had to buy some country records while up there.

However, after a few months it became clear that I had picked the wrong time of year to go looking for work in upstate New York, and the economy was such that I was doubtful that spring or summer would be much better. Holy Trinity Seminary was a great deal for a single student – you could basically work off your tuition, room and board. But there wasn’t much in the way of housing for married students, and nothing that was available or would likely be available any time soon. So toward the end of Lent, I decided that we had to revert to Plan “B”. I continued to take correspondence courses from Jordanville, but I was disappointed that I could not remain there.

My wife had found a good job in Houston, and had started attending the Russian parish in Houston, St. Vladimir. Unlike St. Benedict in Oklahoma, this parish was not a convert parish. Most of the services were in Slavonic (which is sort of like King James Russian), and most of the people there were either from Russia, or their parents were from Russia or Ukraine. My Chinese wife stood out among the congregation, and did not immediately feel welcomed – with the exceptions of the priest, Fr. George Lardas, his family, and also the elderly choir director, Anastasia Titov – who told her that she was a fellow compatriot, because she was a “white Chinese”, who was a Russian from Harbin, China. We later learned that she had worked as a clerical assistant to St. John of Shanghai.

When I joined her, we began attending the Saturday evening Vigil, and there were a handful of elderly Russians (including Anastasia) who had been “holding down the fort” at the kliros, but when they saw that my wife and I were attending regularly, it was as if they said “Lord, now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace,” and from then on we were normally the choir… which meant that I had to memorize the tones and learn the rubrics. We had been in the choir at St. Benedict’s, but being in the choir and following along is quite different from doing it on your own. I also had to learn how to read the Russian in the Jordanville liturgical calendar, because they didn’t have any rubric guides in English, and we had to learn to sing in Slavonic (though I never became very good at singing hymns that were not done regularly).